The history of knife locking systems

blade tang.

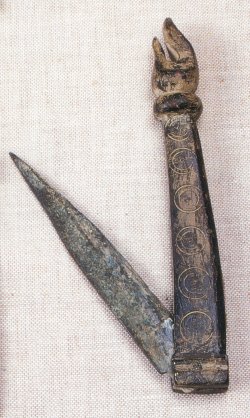

The question is when the first blade locking system appeared. Specialist books on folding knives usually offer lists for diligent collectors, meticulously sorted by manufacturer, production time and place, by mechanism and purpose. But disillusioned, one realizes that the questions about the beginnings of knife locking systems usually remain unanswered: neither who nor exactly when is known. With all due caution and therefore imprecisely, we can say that the first simple systems were spread in the Middle Ages.

In the first system, the friction folder, there is a lever or tab-like extension on the back of the blade which, when working with the open blade, lay on the back of the handle and thus inside the hand or under the thumb. In the second system, a piece of metal (often bronze) on the handle pressed on the tang and thus locked it when the blade was open. A modernized form of this can be seen in the traditional "Windmühlenmesser"( "windmillsknive" in English) Lierenaar knife, which can be recognized by the blued drop-point blade and beechwood handle with the unmistakable iron spring mounted on the back to lock the blade in place.

catch can be released by pulling on the ring.

The locking spring in the handle, forged and elastic, came around 1650. 100 years later, in 1742, Benjamin Huntsman's invention of crucible, or cast, steel made it suitable for mass production.

There were reasons why this took so long: up until industrialization, the production of locking springs was already driving up prices. That's why the farmers' folding knives, which had dominated until then, usually did not need them. Nevertheless, there was a family of folding knives which early on showed a lock that coupled friction and spring power: the Spanish Navaja.

In some pieces (at the beginning of the 18th century at the latest) there was a lug on the locking spring which, when the blade was opened, automatically locked into a corresponding tooth of the blade heel, thus securing the blade. If one wanted to fold it in, the spring together with the locking lug was pulled up by a ring. Then the blade could move freely again. This well-known principle is still used and varied today. Instead of the ring, for example, a spring-loaded rocker arm lifts the locking spring.

Stages of development of blade locking systems

With the industrialization of the 18th century two things happened: the first was the mechanization of the folding knife. Something that US author Bernard Levine described in his book Pocket Knives, explaining how much of the basic design and technology of modern cutlery was developed in France, largely by one man, master cutler Jean-Jacques Perret. In 1771 Perret published a detailed and fully illustrated record of his work in three in-folio volumes, The Art of the Knifemaker (L'art du coutelier,in original), and also his autobiography. Over a century later, “inventors” in America, Britain and Germany regularly received patents for knife mechanisms that they copied line by line from Perret's books.

Second came blades in which the locking mechanism was released by pressing on one end of the locking spring. The advantage was that his design did not require any disturbing external elements such as the ring. From this developed (to put it simply) what is known as back lock/lockback. British manufacturers have been producing such lockbacks since early times.

In Germany, a mass-produced knife probably deserves the credit for having made this locking device acceptable for the first time: the Mercator knife, built since 1867 and developed by Heinrich Kaufmann & Söhne Indiawerk. The rights to this historically significant type of knife are today held by Otter. The Solingen-based company continues to develop the classic knife with new materials. In the beginning, there was a hump at the top of the handle back to press in the spring-loaded rocker.This was soon changed by placing a recess in the back of the handle, over which the rocker and spring could be pressed down with the pressure of a thumb. In 1962 the US manufacturer Buck Knives introduced the 110 Folding Hunter, a folding knife model that set new standards worldwide with its construction, design and backlock mechanism.

But the lockable pocket knives that have been common ever since had one thing in common: you needed two hands both for opening and closing. For this purpose there has always been a blade notch known as "nail nick". The fingernail was inserted into this notch and the force of the fingers could be better used against the spring force when opening the blade. In 1981, Sal Glesser, founder of Spyderco, conceived of a blade with a hump and a circular hole in it: if you grab the knife so that the tip of your thumb goes into the hole, the blade can be opened without having to reach around and without a second hand.

Alternatively, other manufacturers provided their blades with pins protruding from the side or tabs at the back of the blade for the same purpose as Glessers ingeniously simple blade hole.

The development of the locking system that proved to be the most common system besides back lock/lockback was more difficult – the liner lock: a spring loaded liner, or lockbar, rests in the handle alongside the blade. When the blade folds out, the lockbar pops automatically into the now empty area and pushes against the tang of the blade. With a little skill, you can push the lockbar away with one hand and fold the blade. In its current form, this is based on the American Michael Walker's design, who had been working on it since 1980.

However, there were forerunners of internal lockbars: the US manufacturer Cattaraugus developed such a liner locking system (patent, 825 093). Such knives also existed during the Second World War, for example the Camillus TL-29, which was widely used by electricians. 1929 also saw the issue of such a patent in the name of the German O. Altenbach. But Walker's achievement – a hotly debated topic among knife fans – is to have optimized the system in such a way that it became generally accepted, namely by the famous US knifemaker Bob Terzuola (also known for having decisively influenced the "Tactical Knife" family).

Further locking systems for folding knives

Beyond back locks and liner locks, there have been plenty of folding knife locking systems since the 19th century. Some of these can be discovered by researching the patents filed with Google, for example, but by no means everything has progressed beyond the patent stage. Here are some (but not all) systems:

- The Virobloc rotating handle ring secures the blade and blocks the slot in the handle. If the knife is closed, the blade can also be locked inside the handle. The knife manufacturer Marcel Opinel was founded in 1955.

- Also purely mechanical are the Italian “Old Bear” knives from Antonini in Maniago, featuring a no-return rotating safety ring, which inserts into the brass collar to secure the blade in the open or closed position.

- With the frame lock, the lock is not a separate liner that supports the knife, but rather a part of the correspondingly longitudinally slotted handle. The design is credited to knifemaker Chris Reeve with his Sebenza knife.

- The mid lock is a back lock with the release in the middle of the handle back.

the lock engages a ramped tang portion of the blade.

- With Benchmade's Axis system, a spring-loaded lockbar that moves back and forth in a slot made into both steel liners is positioned at the rear of the blade. When it is opened, the lock engages a ramped tang portion of the blade. If the knife is closed, the spring pressure on the bar ensures that the blade does not unfold accidentally.

- The Arc Lock from SOG Specialty Knives is similar, but here the locking element moves in an arc.

- Spyderco's version is called compression lock, which works with a split liner in the handle to wedge laterally between a ramp on the blade tang and the stop pin.

- Deadbolt is the name of the system devised by Flavio Ikoma, in which steel bolts interlock with the blade when it’s deployed. A button at the pivot point, as found on some new CRKT knives, allows for simple blade disengagement.

- Spyderco's ball bearing lock from 2002 wedges a ball bearing between a fixed anvil and the blade tang. Talking about ball bearings, several manufacturers have refined the liners of their folding knives with this as well.

- Worth mentioning is the "Lake and Walker Knife Safety System" (LAWKS), a liner lock system that was invented by Michael Walker and the legendary knifemaker Ron Lake.

The current knife laws in Europe are covered in this article.